“Just as the coronavirus kills people, so does fake news.”

Marc Amorós Garcia

Marc Amorós Garcia is a journalist, screenwriter, television program director, and specialist researcher on Fake News. His two books introduce, deepen, and explain the phenomenon and its impacts on the social ecosystem and our health.

~ What would conceptual distinctions be between disinformation, fake news, rumors, etc?

Marc Amorós: Well, it is possible to distinguish what is fake news from what is rumors and what is a hoax. Deep down, we could say that it is all the same because they are all misinformation and they are all lies disguised as journalistic truth. The hoax is usually something that is not certain; it always harbors some shade of doubt; It is always preceded by “people say that” “someone told me so”, or “I’ve heard”. The dissemination of fake news, on the other hand, intends to give informative certainty about something clearly uncertain.

~ What sets them apart is intentionality.

Marc Amorós: All misinformation is intentional. It is one thing for news stories to become disinformation against the will of their author. There is information that is born in the world of humor, of satire, and that is later spread as real; but the original author had no intention of misleading anyone; he intended to parody something that he considers scandalous or ridicule. Behind all fake news and all information that is disseminated to deceive people, there is always a hidden intention. It can be even the most basic intention: to make money. I mean, there are people in the digital ecosystem who are looking to monetize the spread of false information through clickbait. But there is also the dissemination of false information with ideological or political intentions; which is the intention of trying to mislead us or to manipulate our thinking and our way of seeing reality.

~ Thinking about the trajectory of fake news in the history of societies, can it be said that it is always a contemporary phenomenon?

Fake news appears to be a twenty-first-century phenomenon, but it’s something present since centuries before Christ. I believe that we spread falsehoods since we have the use of reason and the use of the word. Pope Francis says that the first fake news in history happens in paradise and that is what the serpent tells Eva to make her eat the apple… Well, for me it would be for a snake to speak. Anyway, lies or falsehoods and fake news have existed for as long as we have spoken.

Deep down, fake news is nothing more than stories, and tales. And we have evolved as humans around stories that we tell each other. Those stories help us to conform as individuals and as a society. Well, not all those stories tell the truth, do they? That one about the wise men, it’s not a truth, like many others … The Bible tells stories that unite many people and, for some, it is the absolute truth, and for others, it is only some fiction to which many people still give, let’s say, credit. In the end, fake news is stories that help build opinions. And it can make a part of society think in a particular way but based only on unfoundedly false information. Therefore, fake news has always existed and it is not particular to the 21st century.

“Right now, misinformation is being used for ideological purposes in order to wage a war of narratives to impose a vision of the society that we are going to build in the future and what we want in the present.”

~ What are the factors influencing the massive growth of disinformation these days?

Marc Amorós: What is unique to the twenty-first century is the ecosystem in which these misinformations are produced reproduced and realized. Before, misinformation or false news was limited to a tribe, a town, a neighborhood community, or a group of friends, right? What happens is that now there are social networks and this new digital ecosystem that allows the dissemination of information to the whole world at an exponential speed. And now you don’t have to worry only about someone spreading false information but also that he can’t get other people to participate in the chain of virtualization of the information.

What he does is place this information in this new ecosystem that multiplies it and exponentially increases the spread of this false information. Therefore, the most significant change is the existence of this new virtual ecosystem… In the journalistic field, it is neither fake news nor something new. Journalism has been around for a few centuries, and there are documented stories of falsehoods spread by the media and newspapers in the 19th century and in the 20th century… Sometimes, even sparking wars.

~ But we can say there has been exponential growth in the last few decades, right? And is this just due to the development of communication technologies?

Marc Amorós: Yes, there is an exponential growth of misinformation due to three factors: the first is that the digital ecosystem in which we are currently getting informed has led to a democratization of information, both in reception and dissemination. Therefore, there are now more senders than ever, and no journalistic filter exists. It is the opposite of the twentieth-century paradigm of mass communication in which there were senders of information and a large mass of receivers.

Now there is a huge mass of information diffusers and there is also a great mass of receivers, but the receivers that in the twentieth century were a uniform mass are now an individual mass, that is, the information that each one receives is personalized. Now, the senders are also a large mass, but the dissemination of information is also individualized. And this is a factor. There is more propagation of information than ever and that facilitates the dissemination of all kinds of information: the truthful, the good, but also the misinformation, the false ones.

There is another element which is the dissemination of false information. Right now, misinformation is being used for ideological purposes to wage a war of narratives to impose a vision of the society that we will build in the future and what we want in the present. So, through the narratives that are disseminated via fake news, what is sought is to discuss what future we want to have or what future awaits us.

And what’s at stake here is whether it is better to be a native of a place that gives you more rights than a foreigner, whether one race is superior to the other, whether one religion is superior to others, or whether sexual orientation is better than another; or whether or not the threats that we have as humans, as a global world, are powerful enough to take them into account, etc.

I’m talking about climate change, among many other threats. Fake news is being used in this ideological battle to wage a war of narratives to try to impose a dominant vision of the present, a vision of the future. In this large-scale geopolitical war, a battle is also being fought over which governance system is the best we can have as a society: If it is better to have a democracy, with the United States as the first world power, or if it is better to have other governance systems that are more, say, autocratic, even if they are disguised as democracies, as happens in countries such as Russia, China, and others. Therefore, fake news is also increasing its presence because it is being used to try to get in people’s heads to decide what kind of society we want for the next few years.

“People are not looking for facts or truths. What they’re looking for is the confirmation of their personal ideas. So, we have studies that show that when there is information that confirms something that we previously thought, we tend to accept the information as real. It is very difficult for us to accept that we can be wrong.”

~ Have the forms of perception of the means of generating, influencing, and manipulating public opinion changed?

Marc Amorós: In the twentieth century, mass communication was the communication paradigm, and we tried to distinguish public opinion from published opinion. Published opinion was what the media defended or said based on the given information. A different thing was the public opinion that was formed in the societies based on that information. What happened in the twentieth century is that, on many occasions, public opinion and published opinion could be linked. These bridges have been blown up in the twenty-first century because published opinion is not as uniform as in the twentieth century.

The democratization of information dissemination allows any sender to issue any type of information without journalistic ethics or any filter involved. Not only that, but the sender of information does not need to be authorized to disseminate that information. That is, anyone can make a podcast, make a blog, open a Twitter account, or post videos on YouTube saying anything they want. And that makes it possible for a series of information recipients to have more access than ever to all kinds of information. And that allows our information consumption to be very different right now.

Right now, people are not looking for facts or truths. What they’re looking for is the confirmation of their ideas. So, we have studies that show that when there is information that confirms something that we previously thought, we tend to accept the information as real. It is very difficult for us to accept that we can be wrong. Therefore, if I decide to think that the earth is flat, I can find very easily in the digital ecosystem a lot of information that questions the scientific evidence that the earth is round and gives me evidence that the earth is flat – contrary to what science has held for centuries.

If you quickly search on Google and YouTube right now, you’ll find countless materials defending this thesis. This also applies to the coronavirus, for example. Suppose you want to explain why we have this pandemic, where this pandemic comes from, and who are the culprits. In that case, you can easily access a series of information-supporting explanations that help you envision why this pandemic exists and who the bad guys are.

~ So, does this democratization of information completely change our informational consumption?

Marc Amorós: Yes, we no longer go to the information to look for tools that allow us to make better decisions or decisions based on what is happening; we go to the information simply looking for something that confirms what we want to think. This facilitates the dissemination of all kinds of false information because it quickly finds followers.

~ In the same way, is intentionality also plural, not only related to economic or ideological power?

Marc Amorós: In most cases, yes, but not necessarily. Those who spread false information with the simple intention of making money to monetize the traffic generated in the digital circuit can spread false information that is not necessarily ideological or linked to politics. People can also spread false information linked to very primary emotions such as insecurity or fear, for example. If I want to profit from false information, I can find a way by spreading fear about consuming certain products. I can say, for example, that eating cabbage causes cancer, and I can have an active campaign of alleged videos and alleged interviews with alleged scientists who claim that eating cabbage causes cancer. I can also spread false information by attacking a famous supermarket company. If there is a supermarket that is the best known in a city or a country, I can say that a specific product from the supermarket causes hives, insomnia, or a thousand things.

In the end, I’m not spreading ‘ideology.’ Still, I am trying to spread information that very quickly draws the attention of many people and appeals to a very primary, very basic emotion, which in this case is the fear of getting sick. When I activate these levers, I will probably successfully realize that information. The good-natured character that we can all have, that is, if I receive information that warns me that consuming a particular product from a certain supermarket can cause me a series of illnesses just in case, I stop consuming it, and just case, and with my bondholder nature, I share it with my friends, of course, I don’t even want them and my relatives to get sick; therefore, this would be a channel, a possible way of disseminating information false not linked to ideological content.

But there is indeed a lot of false information circulating today that is linked to, let’s say, political and ideological issues. We say political, but in truth, we say ideological. What happens is that each political party embraces an ideology. Everyone knows the orange, green, blue, or red political party defends this ideology. In the background of fake news, the great majority and the great quantity are being used to link them to ideological issues and ideological issues that also have the pretense of polarizing and dividing us as a society, to make us believe that you can only think one way or another; that there is no middle ground, that there is no possibility of divergence, that there is no possibility of dialogue. Ultimately, we build through these ideological narratives, many of which are false and fed through false stories. We build very, very, very polarized societies that are doomed, let’s say, to confrontation rather than understanding.

~ How can we defend ourselves?

Marc Amorós: Well, many elements come into play here; let´s see some game elements. The first and most basic is our intellectual laziness when consuming information. We have turned the consumption of information into something very light. We spend very little time informing ourselves, even if the information consumption occupies us or does not entertain us for a long time. We rarely read beyond the headline. We rarely try to cross-check information. We rarely try to verify sources. We rarely do a job of digging into the information we consume. The younger generations are deciding in practically eight or ten seconds whether to click on a headline or not or whether or not to share it. This fast and furious consumption of information eliminates our capacity for assimilation and reasoning; in the end, our intellectual laziness is one of the factors that play when it comes to explaining why false news is viralized so much and so quickly.

Then, there is another element of the game, which is, let’s say, the illusion that makes us verify that we are right. Discovering that information reveals and confirms what we already think produces a dopamine shot, similar to eating chocolate, having sex, or celebrating your team’s goal in a soccer game. That dopamine shot, that high we have, inevitably drives us to share that euphoria; and share that euphoria as if we were on a soccer field, we would hug the person we were next to that we did not know at all.

Now, what we do in social networks is share them with people we interact with. Here, a third aspect happens: in social networks, we usually interact with people related to our beliefs and our way of seeing the world and things. Little by little, without realizing it, we lock ourselves in an opinion bubble where the information that does not conform to that opinion is discarded, and only the information that confirms what the thought we all share enters.

And when it comes to sharing that information, we are tribal beings. We seek the acceptance of the community and the group. We like to see that others are online with us and in tune. Therefore, we share that information first to reflect our identity and point out, “I’m like that; it’s cool how you are, and I’m teaching it every time I can.” Then you look for that feedback, that “like,” that “I like,” that “I’m with you here” because that reaffirms you as part of a group, as part of a community. And for those reasons, we end up sharing information. We do not realize that this also entails some dangers; it entails the danger of, first, the uniformity of thought, of not accepting that there is thought different from one’s own, and the second danger is the radicalization that uniform thought carries with it.

Studies show that opinion bubbles and people who are most locked in opinion bubbles tend to be radicalized instead of being flexible to other types of information or relaxing their positions. Why? The very pressure of the bubble group leads one to confirm and demonstrate that their beliefs are unalterable, firm, and stronger than ever, which leads to a radicalization of thought. Well, as long as it is a radicalization of thought, one may think that it is not harmful. But of course, when this radicalization of thought leads to an action to demonstrate that we are right and to show that our thinking is the only valid one because that leads us to scenarios such as the raid on the Capitol on January 6 in the United States to demonstrate, or to denounce, or to affirm that Trump has won the elections and that Biden has won fraudulently, and we are going to prevent Biden from being proclaimed president, or many other demonstrations that we can see daily.

“I always say that the news is false but its consequences are real.”

~ Falsehoods that act as truths occupy a very large space in the reality of many people… When these things happen, we are surprised at how they can happen…

Marc Amorós: When these things happen, we are amazed at how they can happen. Many germs of this type of action are in the belief in a series of stories, in this case false, that impel many people in a group, in a community, in a tribe, to take a joint action that is real action, right? I always say that the news is false, but its consequences are real. And this is a real consequence of believing a false story, in this case, driven by a president who does not want to admit defeat.

Look, we are facing a phenomenon that has existed for many centuries but in the dimension in which it currently exists, it is a fairly recent phenomenon, quite young. Social networks have existed for just twenty years, and we have been talking about the danger of fake news since 2015 and 2016, which is when Trump burst onto the scene and polluted the entire environment, especially political and ideological. Therefore, we are facing a phenomenon that is recent in this object of study, and we still need time to find out what possible effects or impacts it may have in the medium and long term.

However, we are beginning to see signs that these impacts are harmful to society. We are seeing how there are societies that increasingly polarize and radicalize their positions, which contaminates and hinders the Agora, the public space for discussion. The public space for discussion is not a place for confrontation but rather for mutual understanding. That is, one goes to the Agora to present their points of view to try to find common points with the divergent ones and to try to create some consensus that allows us to move forward as partnerships.

This, right now, with the rise of false narratives of fake news, we are taking it upon ourselves. It costs a lot to go to a common space where, from respect and from the exercise of listening to the other, it is possible to reach common ground and points of understanding. We are seeing radicalizations in societies of certain groups, which each time feel more powerful, stronger, feel with more right to make their position visible, and not only this, but they feel with a greater right to impose their lie on the truth, say, accepted by others. And this is always dangerous because it puts the informative truth on the same plane as an informative lie, equating it with the “well, I think so, that’s my opinion, my truth and yours is yours, but it’s not good”. Of course, informational facts must have the power to override an opinion, that is, I can think that the earth is flat but if some informative and scientific facts show that the earth is round …

“As citizens, as consumers, we must first be aware that we are informing ourselves in a digital communication ecosystem that is not healthy. That allows the dissemination of the informative truth as well as the informative lie.”

~ What measures are needed to reduce the damage? Educating for dialogue? Education against misinformation?

Marc Amorós: Well, this is the big question, right? Let’s see who has the magic solution here. I’m after Harry Potter to see if I can count on him, but I see that Harry Potter is fake too, and that’s why I’m screwed with it. Let’s see, magic solutions, I can’t think of any. I believe that we can take small steps to help us understand the phenomenon and protect ourselves from it. As citizens and consumers, we must first be aware that we are informing ourselves in a digital communication ecosystem that is not healthy. That allows the dissemination of the informative truth as well as the informative lie.

Before in the twentieth century, you went to the media and gave you, let’s say, that halo of protection against bad information or false information. This does not mean that it did not happen, because it happened too, but not on this scale. The digital ecosystem does not guarantee the dissemination of the informative truth, but rather facilitates and favors the diffusion of the informative lie without any objection.

Therefore, we must first be aware of it: we are informing ourselves in a communication ecosystem where the news is not one hundred percent reliable. The second step is to act and analyze the individual information consumption that each one has, how much time I dedicate to the information, with what will, with what dedication, and with what spirit. And then what do I do with the information I receive? Whether or not I share information, because I share it, if the information I share. I am one hundred percent sure that I am contributing to the dissemination of good information or the dissemination of false or fake information.

I believe that each of us has to exercise self-criticism. In Spain a study was carried out: they asked two thousand people if they believed they could detect false news. Sixty percent said yes, they believed they were capable, and that same sixty percent said they believed they were more capable than others, that they had self-confidence and thought they were much better than others. They did a test and in the end, they only got three out of twenty correct, that is, the percentage was less than fifteen percent. Therefore, we believe we are more capable than others of detecting false news, and we think that it will not happen to us, but deep down, we are more vulnerable than we really think.

Therefore, you must first become aware of it; then, you have to try to verify the information you receive, of not getting carried away by the most primary emotion and impulse. Either of fear and insecurity but also indignation, because fake news also plays with indignation, they try to provoke the anger of others, on the contrary, to reaffirm those who think like me. Then we have to do some homework. Some individual duties.

Then, at the level of promoters or disseminators of information, the media fight against false news in an increasingly evident way and try to incorporate data verifiers in their newsrooms. They try to make this journalistic work visible, a work that should be intrinsic to the profession, but they try to make it visible. I think they should take more steps. The media are still very slaves of speed; they are very slaves of click, of that economy of attention in which the digital ecosystem has locked us up, and then there would be the third objective, which, for me is the most complicated step that it is: I believe that disinformation, rather than censorship, what it needs is ethics.

To put ethics in this ecosystem, we need, on the one hand, the technological platforms that facilitate the dissemination of this type of information to commit to having ethical standards beyond what they consider incitement to pornography, violence, or hatred that now are brazier than they place; I think they could take steps beyond not allowing the purchase of spaces on their social networks without controlling what information is disseminated; They should let’s say, help us to pursue the source of disinformation, where it comes from, who spreads it, and close those speakers or those diffusers. Then, there was another step within the ethical world that would be an ethical commitment on the part of all the political parties and influential social and economic strata of the countries to commit not to use disinformation as an electoral weapon, as a political weapon.

This is a complicated step, a difficult step, but I think we should go more along these lines and not in the line of trying to spread messages from the political elites or government officials to tell us that we must censor, that we must control the flow of information. Because this refers to times or systems where there is only a single informative voice. And in societies where democracy has been able to exist for a time and where the right to information and freedom of expression has been won, well, I believe these are scenarios to which we would not like to return.

~ One of the problems we have now is that in this digital ecosystem, the dissemination of information camouflaged from the media has multiplied, especially on social networks.

Marc Amorós: A large number of profiles or digital media have appeared with the appearance of digital newspapers and not all these media were born to inform. Many others have been born directly to misinform. After all, they live on subsidies from organizations, governments, and lobbies because they act at the dictation of political parties that are in government or are in the opposition and that pollute the journalistic space in the diffusion of information. Then, what happens to journalism, or to the journalistic communication media, is that they suffer attacks on two fronts, and fighting simultaneously on two fronts needs a very large army, right?

The first front is fake news. That is when you have a product that is supposed to be of good quality and other diffusers enter that are spreading that same product, with the same appearance but with poor quality or questionable quality, and it is difficult to discern which is the good product and the bad product. Instead of talking about information or news, let’s talk about meat consumption, for example.

Imagine that the meat industry spreads good meat, with codes and regulations that allow you to go to the supermarket or the market to buy it and consume it without arguing about where it comes from and in complete safety. Well, now imagine that other diffusers enter the meat industry, that we do not know who they are, that they begin to flood the meat market, and that not only does it offer it cheaper but that it offers it for free, but that meat we do not even know if It comes from sick animals, from well-fed animals, or if it is expired from other countries and if it is in a freezer or a refrigerator, we do not know for how long.

Now, one wonders what kind of meat I will consume. What the consumer wants, in the end, is a guarantee, and they want to go to a place to consume good information. And here is the media opportunity. This is the front in which the media fights against fake news to claim the quality of its product. It is good to label what is bad, but it is also good not to forget to put in value and put in a lot of effort so that the quality of your product is indisputable.

The other front that journalism is fighting against is the systematic attack by many political forces that question the veracity of the information to impose alternative stories that suit their interests. Those are alternative stories fed by fake news. Trump said: “There are some facts and some alternative facts.” The “alternative facts” are the vision that I want to impose on what is happening because they suit my interests and the journalistic account I classify as false, as a liar, and as adulterated. Of course, that attack is a very frontal attack, very dangerous, usually from a very powerful speaker. And that is another front against which the media has to fight.

~ And all this happens in an environment that is not at all favorable to the media.

Marc Amorós: The media used to have something that had value, and people gave it value. That is, you bought a newspaper in the twentieth century, and what that paper put was very important and very relevant. Right now, the consumption of newsprint is disappearing, and the digital environment is not giving value to information. First, because anyone can disseminate information, and second, because this idea has been established that information on the internet is free. So journalism has believed the internet milonga that with the generation of traffic and the capture of the attention of users, there will be several advertisers hitting each other for advertising, for advertising in their murals, that this is going to report an exponentially higher amount of income than they had in the twentieth century. But that is not happening.

Then, the media have to value their journalistic work through quality, through not being political, that is, independence, and then value, in the face of their consumers, that the information has a price, it has a value, and that it is necessary to establish a value for money and that it is good that the consumer is willing to pay. When someone is willing to pay for something, their intellectual laziness is less, and their capacity for effort is greater. When someone consumes something free, they consume it, but since it is free … if Netflix or any streaming platform were free, surely we would not be so successful, and we would say that all their series are shit and we are not interested. Now, it turns out that as it is paid each month, whoever has that streaming platform then says “Hostia! I’ve seen this and I like it, I’ve seen that and I liked it ”. I believe journalism must take these steps to vindicate its work and regain a social trust that is slowly losing due to those three significant battles that it must fight.

~ Based on all these contexts and the historical process, can we imagine how information consumption will be soon?

Marc Amorós: This is a big question: imagining how we will consume information in the future. Let’s start from the present: the digital environment is no longer dominated by the big media or big news corporations. It is beginning to be dominated by micro-disseminators of information that have a significant influence. They are what we would call influencers. Today, some influencers have a much larger audience than the prominent newspapers in many countries. More and more information can be personalized based on interests.

The twentieth century manufactured a newspaper or a series of information that was the same for everyone. That was mass communication: a few information disseminators manufacture information for many people simultaneously. The twenty-first century and the digital environment will allow a series of information disseminators -many- that will disseminate information, but not the same information for many people, but will personalize the consumption of information.

That does not mean that for that personalized information, there are not many people, even more viewers than a newscast, or even more readers than a newspaper, who consume it because they share that focus of interest. But what there will be the personalized consumption of the information, that is, depending on my interests, I will decide if I want to find out about the economy, politics, society, or events, crimes, sports, and I will decide if I want only football, or I want basketball, or I want water polo, and that personalization of the information will cut a scenario that we will see how we do with it, or how we deal with it; that the information that you will consume and the information that I will consume will not be the same. With this, the vision that I will have of what happens will undoubtedly be different from the vision that you have. With this, better new journalistic elements have to be born that confer a somewhat global vision of what happens beyond the personalization of the information.

“We know that fake news has an impact on our brain in the long term or in the medium long term, which is the concept of familiarity. Goebbels already used it in Nazi propaganda in his time, which is when the news is familiar to us but we do not even remember where we read it from, where we heard it from, nor do we know if that information was false or real at that time.”

Therefore, it may be that two scenarios coexist: the scenario of macro journalism that tries to contextualize on a large scale what happens intending to try to build a public opinion or a joint vision of society around a topic, which in the Middle Ages towards the church or the priests did the pulpits of the churches, but then they open, let’s say, the micro information and the micro consumption of personal information that each one will have. And everything will be journalism, that is, journalistic content, which will have to be satisfied, but we are likely in this dual scenario.

We know that fake news impacts our brain in the long term or in the medium long term, which is the concept of familiarity. Goebbels already used it in Nazi propaganda in his time, which is when the news is familiar to us, but we do not even remember where we read it from, where we heard it from, nor do we know if that information was false or real at that time. If we take that information and have adapted or accepted it as real today, it is likely that from here a time, a few months, a year, two years, five years, when we remember that information, when we go to the hard disk of our brain to look for it, we are not able to detect where we consume it, where it came from, well, the brain tends to take something we remember as true and we are not very clear that it was false, since the brain tends to think that everything we remember has happened.

If you anchor the memory with the concept of false, when you recover it in the future, you will likely say, “Ah, yes, I remember that, and that was false.” But if you do not anchor the concept of false, because the moment you have consumed the information, you have taken it for true, you have not received a verification telling you that it was false, or when it has reached you, you have not wanted to hear it, you have rejected because it is likely that in a while when you go to your memory to look for that information, you will recover it as something that has undoubtedly happened.

That happens to us with events … those of us who already have a certain age when we remember when we were children or young people because we think that it was that way, but then when your mother comes and says, “Well, not exactly, that It was otherwise ”, but you remember it that way. If I had to tell someone about it without your mother being present, I would swear that it happened that way.

Well, that a bit also happens to us with information, and this is a harmful effect that we will discover in the long term when there are people who, when information from the past is recovered, well, they take it as true being false.

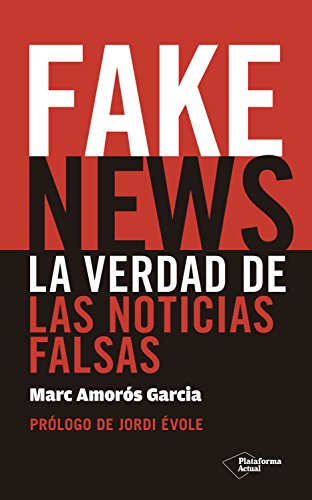

Fake News. The truth of the false news

Fake News. La verdad de las noticias falsas

Publisher: Plataforma Editorial

ISBN: 978-8417114725

192 pages

2018

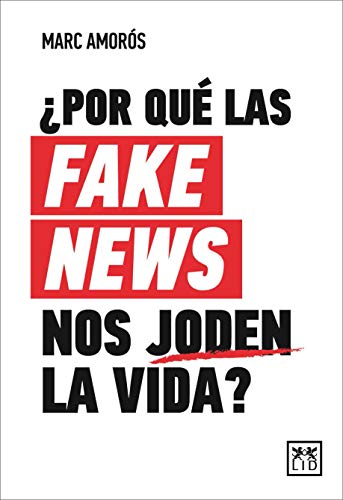

Why does fake news screw up our lives?

¿Por qué las fake news nos joden la vida?

Publisher: LID Editorial

ISBN: 9788417880415

256 pages

2020